Classic French cooking approaches steak temperatures with a simple elegance. There are four basic ways the French order steak. Bleu means very rare, quickly seared on each side. Saignant, literally meaning bloody, is a bit more cooked than bleu, but still quite rare. À Point implies “perfectly cooked” (the closest to our Medium Rare) and Bien Cuit, well done. The French don’t fuss with superfluous language around ordering meat; you like your steak one way or the other. The behavior is anchored in a tradition of respect for the chef’s expertise and deference to the talent in the kitchen.

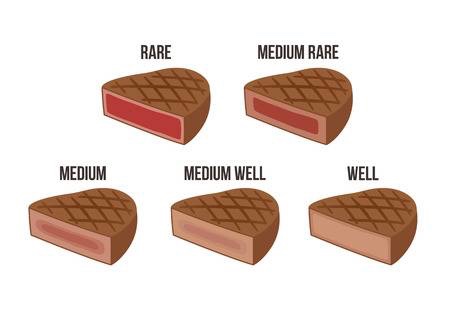

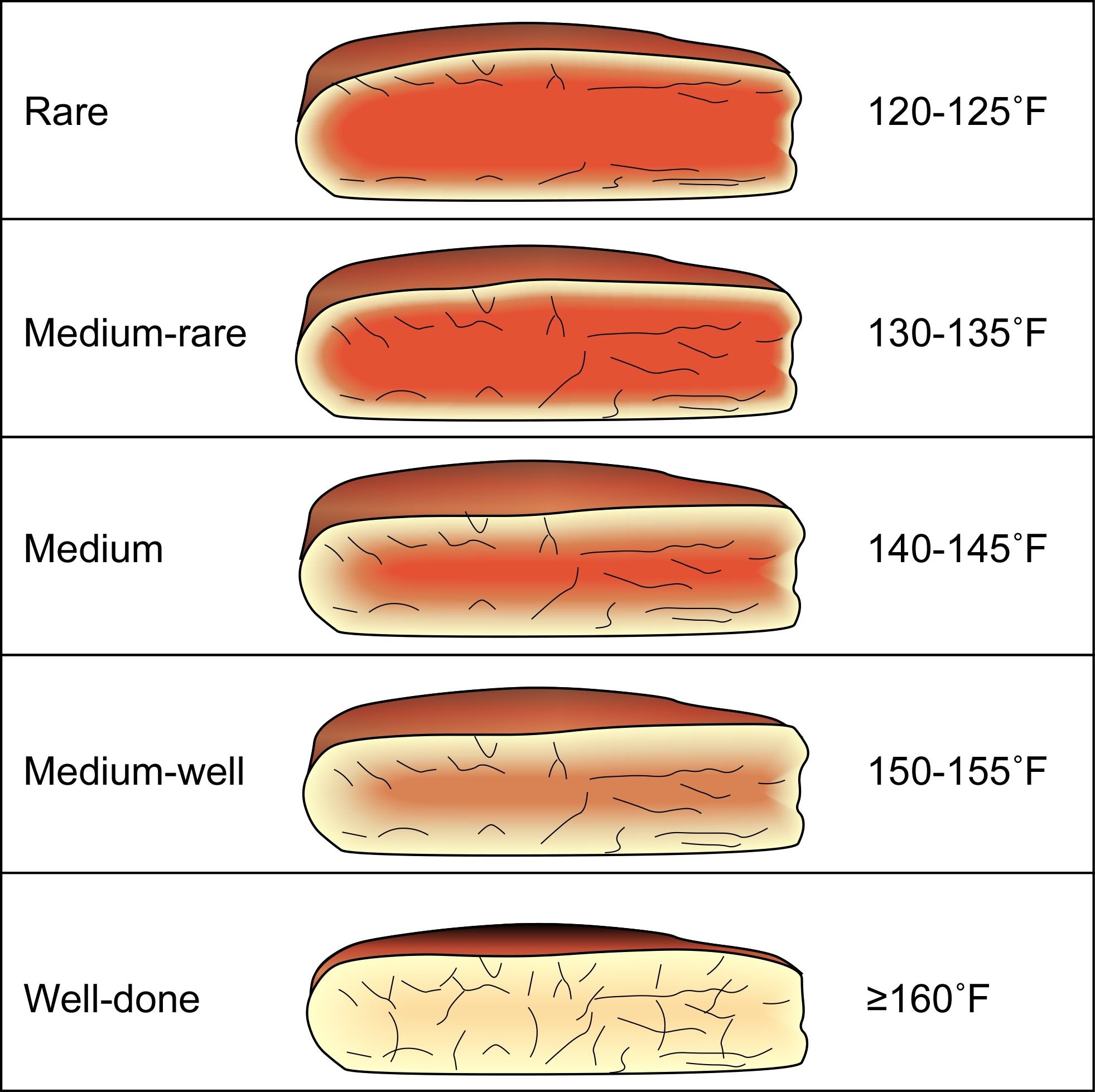

Americans aren’t able to speak so abstractly about cooking meat and are more suspicious of the chef’s faculties. To make steak temperatures more scrutable, restaurants (with the blessing of the USDA) devised a vernacular to help diners better understand the different gradations of doneness. The approach is rather dogmatic with five concrete meat temperatures, now ubiquitous: Rare, Medium Rare, Medium, Medium Well and Well Done. Restaurant chefs have adhered to this scale for generations but they are a constant source of headaches for hospitality professionals. No matter how streamlined these guidelines have become, there will always be differences in perception around how we should define them.

Today’s diners are becoming increasingly nuanced about how they like their meat cooked. As palates become more sophisticated, defining proper meat temperatures has evolved into a significantly more complicated conversation. It’s disturbingly common to hear guests request “plus” temperatures, meaning they want their meat cooked a shade in between two standard ones. “Medium Rare Plus” implies they like their steak cooked a little more than Medium Rare but not quite Medium. Unfortunately, most restaurant kitchens are too busy to handle this level of specificity.

Trying to make guests happy who order their meat cooked outside of the standard spectrum can drive servers—and chefs—to madness. If we insist that guests adhere to the accepted scale, we increase the likelihood that they’ll send their food back. If they’re unhappy with the finished product, they’ll blame us for not making enough of an effort to understand their preferences. If we allow them to order fabricated steak temperatures that don’t exist, we must face the rage of an ornery chef who bristles at anything that strays outside of protocol. As with many hospitality conundrums, we’re always caught between a rock and a hard place.

A restaurant kitchen isn’t an artist’s studio; it’s a factory. As a guest, you have a responsibility to understand that not every element of your dining experience is customizable. When you dine in a restaurant, you are enjoying plates or food that were engineered to be efficiently served simultaneously to a dining room full of hungry people. Expecting your initials monogrammed on every dish shows a lack of respect for the orderliness that is necessary for a cohesively functioning kitchen.

If waiters could somehow escort every guest who ordered “Medium Rare Plus” into the sweltering kitchen to explain to the grill cook how they like their steak, not a soul would ever ask for it that way again. The power that many guests feel when it comes to the peculiarities of cooking their food is in the luxury of not having to deal with the shame of facing the sweaty cook who’s making it. Good guests won’t abuse that power.