The tragic and sudden death of Jamal “James” Kent, the venerable chef and restaurateur behind New York City’s Saga Hospitality Group, sent shockwaves through the restaurant world last week. Tributes to the 45 year-old chef, who died of a heart attack on June 15, flooded social media, praising his compassion as a leader, generosity as a mentor, and stature as a chef. Aside from Anthony Bourdain’s shocking death six years ago, I can’t recall a restaurant figure whose passing was met with such widespread sorrow. Some prominent figures in the restaurant industry, like Daniel Humm, who presided over Kent’s rise to culinary stardom at Eleven Madison Park, struggled to find the right words. “The world wants immediate statements and ‘favorite moments’ of us,” Chef Humm posted on Instagram. “The truth is that I’m speechless.” When talented chefs like James Kent die young, language can be an inadequate tool to express grief.

I was fortunate to have worked with James Kent in the early 2000’s at Babbo in New York City’s West Village when he was a green, fresh-faced line cook. James was introspective but affable—he was a cook’s cook—well-regarded by both front and back-of-the-house. To be so universally accepted was unusual in a cutthroat fine dining restaurant like Babbo. Young cooks often harbored resentment toward waiters who made more money than them without getting their hands dirty. But James respected everyone’s role equally. He also wasn’t the vindictive type. My first meeting with him felt a little threatening; he had a knowing smile with the slightest smirk and stared you down when you spoke. But after a while, you became accustomed to the intensity. He didn’t just listen to people, he wanted to understand them. It was his greatest strength as a leader.

Although I’d only seen or spoken to James intermittently in the twenty years since we’d worked together, I felt the sorrow of his death profoundly. Inexplicable losses like his are always difficult to process, but it feels like it cuts deeper when a chef’s life is cut short. In grief, we learn that chefs like James are multi-faceted beyond their culinary achievements—in his case, an avid painter and graffiti artist, a hip-hop aficionado and scholar, a philanthropist, and marathon finisher. He was a proud husband, father of two, and mentor to scores of young chefs. Kent’s food, although universally admired by his peers and honored with many of the industry’s highest accolades, was an afterthought in the many heartfelt eulogies.

When young chefs pass away unexpectedly, our minds naturally drift toward awful contingencies. Concerns about suicide aren’t unreasonable given the sordid history in recent decades of chefs taking their own lives, especially in the ultra-competitive world of fine dining. But when death comes naturally, as it did in Kent’s case, it still feels unnatural. We’re left wondering how much the arduous lifestyle of a professional chef may have contributed to the conditions surrounding his death. “At the end of the day, this is a call to make sure that we’re all taking care of ourselves,” said Gregory Gourdet, chef of Portland’s Kann Restaurant, in an interview with The Oregonian after Kent’s death. Gourdet and Kent had recently announced a partnership to open a fine dining restaurant together inside the forthcoming Printemps, a Paris-based department store, opening in lower Manhattan next year. One thing is certain, James Kent died doing what he loved: cooking.

This past March, another prominent young chef in Detroit, Maxcel Hardy, passed away unexpectedly. In addition to his successful restaurant concepts like COOP Caribbean Fusion and Jed’s Detroit, Hardy also founded a local non-profit to fight hunger and mentored the city’s underprivileged youth. In 2021, The New York Times named Hardy one of the 16 Black chefs who are changing the industry, along with The Grey’s Mashama Bailey and Compère Lapin’s Nina Compton. Like Kent in New York City, Hardy’s impact on the community in Detroit transcended his restaurants. His food was only a small fraction of his legacy.

When we lose chefs like Kent and Hardy, it feels like they’ve been cheated out of reaching their potential. To succeed at such a high level requires Herculean sacrifices—dedicating every waking moment to the craft of becoming a chef, enduring long work hours, financial duress, and extended absences from family. Chefs spend so much time and energy pleasing others that to be robbed of the fruits of their labor makes their premature passing feel even more cruel. But it also feels a little bit like we’ve cheated them. Our expectations of young chefs are higher than ever. Diners scrutinize a chef’s restaurants like food critics instead of supporting them like adoring fans. Underneath the sorrow, some of us are left feeling like we could’ve been more nurturing toward these young chefs who gave us so much. Did we take more than we gave back?

Losing chefs in the prime of their careers doesn’t feel all too different from losing iconic musicians—like John Lennon, Janis Joplin, Whitney Houston, or Prince—who died young. We can only imagine the kind of glorious music they would’ve made if tragedy hadn’t taken them too soon. The way that great musicians channel their feelings through music, chefs learn to speak through their food, filling the plate with pieces of themselves. They learn to cook with love. But cooking with love when the air conditioner is broken, the linen delivery is late, and the dishwasher walks out in the middle of service, is something only few chefs have the grace to achieve. According to the wealth of remembrances from colleagues and loved ones, Chef Kent not only cooked with love, but he created an environment for others to do the same.

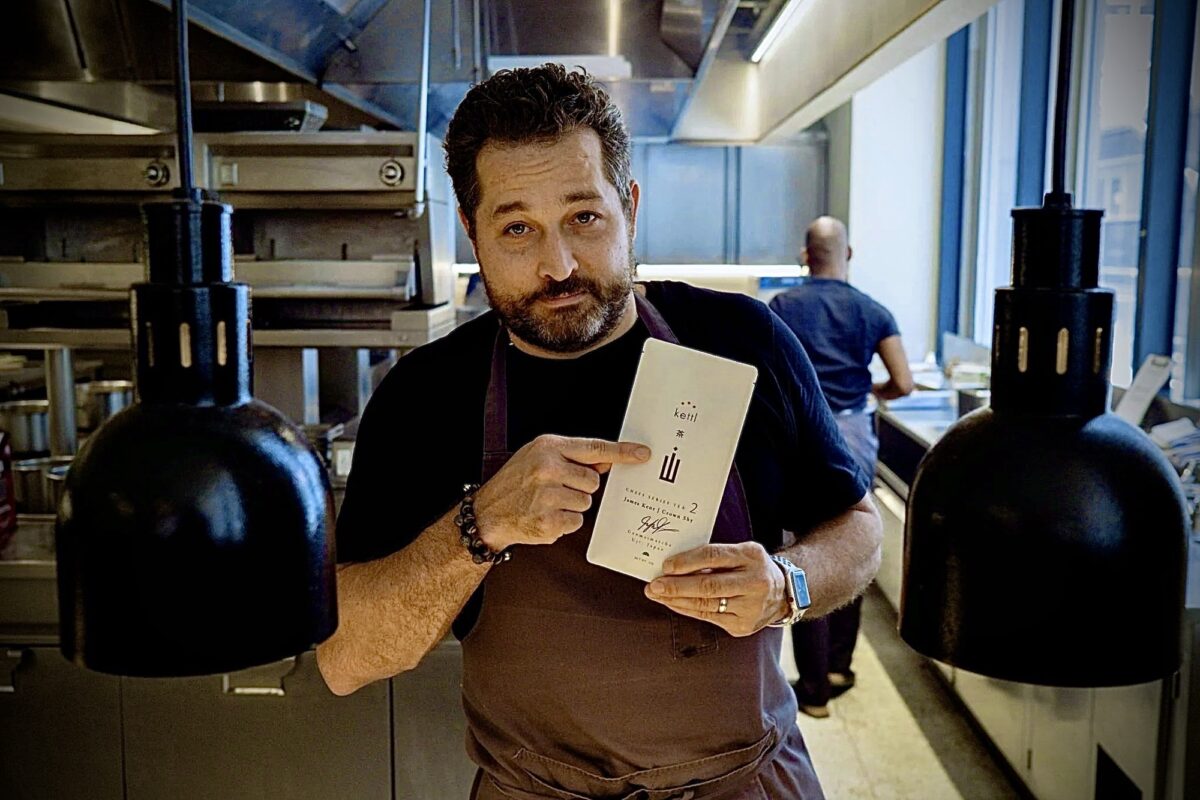

The last time I saw James was about five years ago, when he’d just opened Crown Shy, his modern American bistro nestled inside an art deco skyscraper in the financial district. Even though we hadn’t seen each other in over a decade, we casually reminisced about the Babbo days as though no time had passed. In his impeccably starched chef’s coat, he seemed more intimidating now—like he’d grown physically larger. But he still had a way of putting you at ease. With all that had transpired in his life, the Michelin stars and World’s 50 Best Lists, he was still just a humble cook. His food was always an extension of himself, but he never put himself or his food above the team or screamed for attention with superficial, cheffy flourishes. When someone cooks from the heart the way James did, everyone who dines at his restaurants feels a deeper, more personal connection with the chef. It isn’t because he changed the way we think about food, but because he reminded us why we love to eat. Chefs like him are a rare breed.