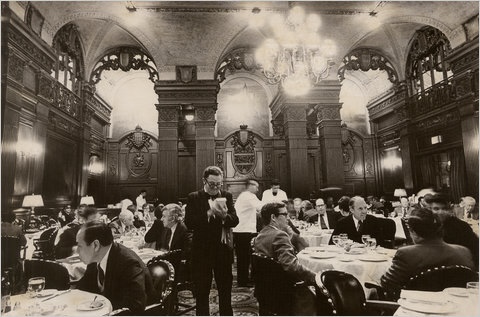

Though “jacket required” policies are far less common today, many restaurants still mandate proper attire, especially in fine dining circles where archaic dress codes stand as symbols of prestige. Some restaurant owners view them as a way to curate ambiance in the dining room — as with Angie Mar’s new Les Trois Cheveaux in New York City — but it’s increasingly unclear exactly whose interests these policies serve. As American dining habits skew more casual, dress codes are becoming increasingly anachronistic. Much the same way that going to the theater or flying in an airplane have lost the glamour they once had, restaurants — even the fanciest of the shmancy — have become more populist. Legislating style feels out of step with modern cultural norms.

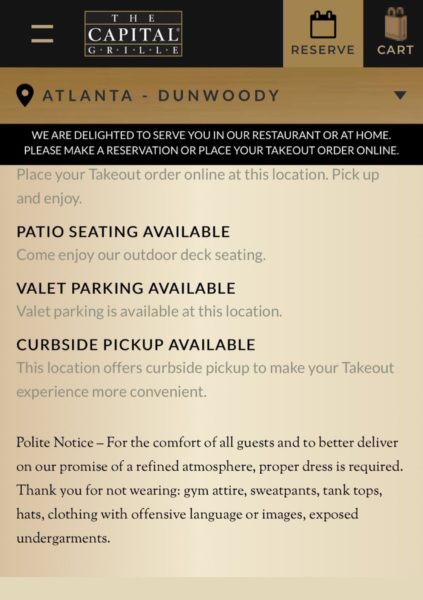

Dress codes also have a sordid history of being discriminatory. Such was likely the case this past week when the former mayor of Atlanta, Keisha Lance Bottoms, was denied service at Capital Grille for arriving to the restaurant wearing leggings. It appears Capital Grille offers a “polite notice” about the policy on its website, saying that “for the comfort of all guests and to better deliver on our promise of a refined atmosphere, proper dress is required.” The disclaimer goes on to explain that this applies to: gym attire, sweatpants, tank tops, hats, clothing with offensive language or images, and exposed undergarments.

There’s a lot to unpack here, but the part that sticks out most is the restaurant’s “promise to deliver a refined atmosphere.” This statement is so loaded with potential biases that it’s impossible to believe that Mayor Bottoms is the first victim of the fashion police at this Capital Grille. Also, who gets to set the standard of what constitutes “refinement” in a Capital Grille or any restaurant for that matter?

As a server working in fine dining, I’ve had customers comment to me on the appearance of others they consider underdressed, and it’s always felt awkward to be on the receiving end of those comments. Why are these people concerned about the way other guests look? Is a more casually-dressed neighbor somehow compromising their dining experience? The standards of refinement — like not wearing hats indoors — are generally faded remnants of a bygone era of Emily Post-style attitudes toward dining etiquette. Enforcing rules in restaurants is often necessary, but it might be time to update rule book.

Of course, all of this belies a deeper question: Does a restaurant have an obligation to ensure that everyone who enters is dressed “appropriately”? If it does, how do they measure what’s appropriate and what’s not? Restaurants that have dress codes will likely argue that these policies are designed to protect all guests from exposure to attire that is obscene or makes others uncomfortable. It isn’t about fashion, they’d say, as much as it is about regulating common decency.

But we’ve also reached a point where fashion isn’t standard anymore, and formal attire is far less common in restaurant settings. Men rarely wear blazers or suits out to dinner unless they come directly from work or it’s a formal occasion. Women might wear dresses, but it’s because they want to, not because they’re worried they’ll be shunned if they don’t.

While it’s difficult to prove these policies racist, it likely plays a role in Mayor Bottoms’ situation and others. Dress codes have often been used to discriminate against marginalized Black and brown people whose style might not fit with mainstream white standards. Numerous photographs have already surfaced on social media of white women outside of Capital Grille wearing leggings and men dressed in athletic wear or gym attire.

Last April, The Ashford, a bar in Jersey City, was accused of discriminatory practices by a Black patron who claimed he was refused service for wearing sweatpants. After being denied entry, he witnessed numerous white customers dressed similarly allowed in. A few months later, The Turkey Leg Hut in Atlanta sparked controversy when it announced a dress code that forbade “excessively baggy or sagging pants.” The restaurant’s Instagram post (deleted soon after the announcement and eventual backlash) indicated that the Turkey Hut “is a family friendly restaurant.” Skeptics were quick to point out that the co-owner of Turkey Leg Hut, Lyndell Pierce, had been arrested earlier in the year for allegedly pistol-whipping a man at a local bar.

It’s unfair for owners like Pierce to put their staff in the uncompromising position of policing their clientele’s appearance or determining who is worthy of entry. It’s a difficult ask to charge staff with providing warmth and hospitality while at the same time scrutinizing guests’ attire. Empowering employees to enforce flawed policies opens the door for flawed outcomes.

Dress codes also violate the most basic tenet of good service: extending a warm welcome to everyone without prejudice. I can tell you from my years of experience that customers are rarely understanding when a staff member asks them to remove a hat or tells them that their attire doesn’t meet the decency standards of the restaurant. Most react defensively and feel personally attacked. I’ve been asked to remove my hat myself as a guest, and it seems more pretentious now than it ever has.

Fashions change and restaurants should acknowledge that instead of trying to force people to dress like some mythological, idealized version of the past. There were times in American history when certain races were denied service in restaurants simply because of the color of their skin. Restaurants that spend so much energy trying to recapture the glamour of the past —while at the same time inviting discrimination — are inadvertently capturing the less glamorous parts of the past, too.